Data on infant immunization targets – coverage (%) for Hepatitis B (HepB3) and Diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DTP3) immunization coverage among 1-year-olds (SDG targets 3.3.4 and 3.b.1) is available for twenty-six countries but not in sex-disaggregated format.

Data on infant immunization targets – coverage (%) for Hepatitis B (HepB3) and Diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DTP3) immunization coverage among 1-year-olds (SDG targets 3.3.4 and 3.b.1) is available for twenty-six countries but not in sex-disaggregated format. The average for the Western Pacific Region was 93% for Hepatitis B and 97% for the DPT3 vaccinations (2017).

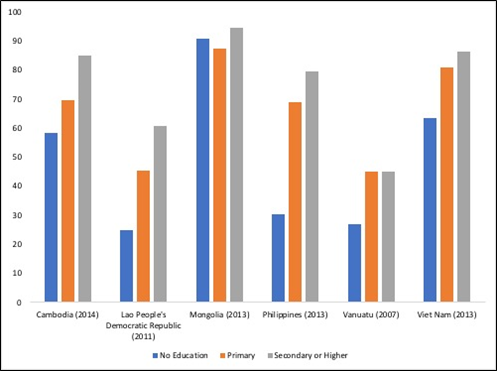

As discussed throughout, improved education for women is associated with better health for them, their children and their grandchildren (201). Figure 16 highlights differences in the impact of inequalities in maternal education for children living in different countries in the Region (15,202–206). For example, there is a much steeper gradient in inequalities for children born to women with no education in the Philippines, the Lao PDR and Cambodia compared to Mongolia where the difference between all three levels of education is far less. In Mongolia however the children of mothers with no education have a slightly higher coverage rate compared to children whose mothers have primary education. This might reflect the impact a campaign to reach mothers with no education which may have unintentionally created inequalities among the children born to mothers with primary education.

Figure 16. Full immunization coverage rates among 1-year olds (%) by mother’s education level, selected countries, Western Pacific Region, various years (15,202–206)

References

Feedback

Notification